By Heather Sansom

Most sources agree that core strength is important for riders of all disciplines. In fact, whether you practice a sport or not, core strength is a significant key to athletic performance, good posture, and joint and spine health.

A strong core is especially important because riders ride mostly with the torso. Whether you realize it or not, your limbs are completely secondary aids to your seat, weight and torso orientation.

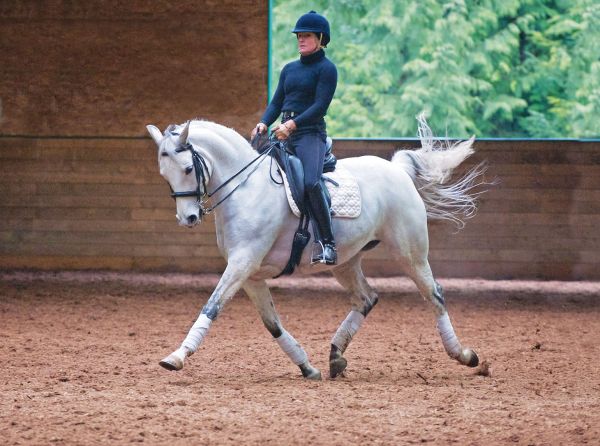

For example, observe a para-equestrian such as Canadian Olympic gold medalist Lauren Barwick, who is paralyzed from the waist down. In addition to competing as a para-equestrian, Barwick rides in open FEI levels. She and similar riders show that balancing on your horse and giving correct and effective aids depends less on use of limbs as torso position and usage.

Para-equestrian riders like Lauren Barwick prove that core position and weight are the most important and effective communication tools with horses. Horses will listen to a rider’s seat and torso position over leg and hand aids. Photo: Robin Duncan Photography

The impact of your limbs on your horse’s way of going is completely secondary to that of your seat and torso. If confused between a leg aid and a seat aid, your horse will follow your seat and weight. This explains why he may seem to drift in one direction even though you are giving him leg aids to the contrary. In clinics and private training, I constantly see riders who think they are giving aids in one direction, but their torso position is giving a contrary aid which the horse obeys instead. For example, they may be trotting on the left rein, but the rider’s shoulders are pointed away from the circle so the circle looks like an octagon. This happens because, instead of bending inward, the rider’s body position is telling the horse to orient his body away from the circle.

It can be helpful to have a friend or your coach check your alignment and weight shifts. In addition to lateral weight shifts (side to side), you can tip forward, which shuts down the horse’s movement and puts him on the forehand; lean back, which shuts down the horse’s movement and causes his back to hollow; or rotate asymmetrically (e.g. one shoulder back more than another), which interrupts the horse’s ability to move with straightness. Tipping forward with a weak core is not the same as deliberately putting your body in two-point position. Even though the seat is in the air and the back is tipped forward, a correct jumping position must include a strong core to help the rider maintain hip and heel alignment, and grounding through the seat. Otherwise, the rider would be falling onto his horse’s neck or involuntary shifts of bodyweight might cause the horse to bear onto the forehand.

Your bodyweight distribution and motion affects your horse’s movement with the tiniest shifts. Muscles in your core are like a sheath of muscles wrapping your torso and hips. They layer like plywood, some of them orienting horizontally, some vertically, and some responsible for angled or rotational force. Most of them have a higher percentage of slow-twitch muscle fibre, which means they are built for endurance, not fast movement, because they have to stabilize your body while your limbs do other tasks that generate load to your spine area.

Your core muscles control your hip mobility and stability sitting on your horse, postural stamina, and independence of shoulders and hips. They are responsible for your control over seat and leg placement, protecting your spine so that it is free to absorb your horse’s motion without injury, and returning you to straight symmetrical posture after a dynamic interruption (such as posting trot, a change in gait, a spook, or a fence).

Your core muscles are the bridge connecting your upper and lower body and providing an “anchor” for your shoulders and your legs. Many riders with pulling hands often have weak core muscles. The pulling hands are the body’s compensation for its inability to stabilize the position through the core.

I consider the rider’s core to be a foundational training area, similar to the first levels of the training scale used in dressage. If you do not ride dressage, think of a scale of tasks your horse needs to be competent in before he can move to the next level. All horses need to move with good rhythm. Even though it is a factor from a very early stage, you never get beyond it: it is always important. If your horse gets to a higher level in his training and loses rhythm, then you have to go back down to basics. Core strength for the human athlete is similar because without it, your body starts to use compensating motion patterns to perform tasks you ask of it. Compensating motion patterns cause hypermobility or stimulation of other muscles, which causes muscles and joints to be used more than they were meant to be or in movements they are not best suited for. This introduces unnecessary wear and tear on that area. For example, a rider with stiff hips and weak lower abdominals will have a tendency to absorb more of their horse’s motion in their lower back, which can lead to pain and strain over time.

Another common example is the rider who has a weak core and is not maintaining correct pelvic position. As a result, the horse’s motion causes the rider to lose balance a little, which their body manages by tightening their inner thighs. This rider may have to use artificial aids to induce the horse to move, because the tight inner thighs create leg pressure that becomes “white noise” to the horse and so he can’t “hear” normal leg pressure anymore.

The importance of training the core for a rider just makes so much sense. In fact, when I am working with clients who are under time pressure, I will frequently advise them that if they have to drop exercises from their schedule in a given week or during a hectic show season, the two activities they should keep without fail are exercises for flexibility and core strength. One reason is that both stretching and core work can be done anywhere, anytime, and while wearing just about anything, which makes it really easy to keep them in your life when you are extremely busy.

What is less clear for many people is exactly what to do about core strength. It’s not as easy as just saying: “Work your abs.” When I am designing a training program at a clinic or for a private client, I will emphasize different exercises and degrees of core training that depend on several factors:

- the individual (age, fitness level, physical issues);

- discipline requirements (for example, cross-country fences introduce much heavier demand in more directions on a rider’s back than other events);

- the amount of time and tools available to the rider for training.

However, most riders can benefit from any core training as long as it is well-rounded enough for a rider, consistent, and keeps them interested in doing it faithfully. To get results, you also need to always push the envelope just a little bit further each time you work out.

Most people can have a noticeable impact on their core strength by starting off with five minutes a day of training. Because core muscles have a lot of endurance, time is your best ally in training and you must use it if you want to avoid injury. You are better to train a little but consistently five days a week than to do big core workouts sporadically; the big sporadic workouts place you at more risk for overload leading to injury. Small incremental increases in daily core training over time will have a positive impact on your riding in the first week, without you risking injury or making major lifestyle changes to get results. Riders who do some core training on a regular basis get the added benefit of better posture and spine health, and better back support for any activity they do.

You can find core exercises almost anywhere these days. Knowing how to put them together effectively for your riding requirements makes all the difference. Here is the formula I use for designing core workouts:

1. If you are just starting out, train for just a few minutes each day. When your core workout starts to take 15 to 20 minutes, you can drop it to several times a week. When you reach a good base of core fitness, you can maintain it with just a couple of core training sessions a week because you will have also taught your body to integrate core stabilization into everything you do.

2. Include a mix of active movement exercises and isometric exercises. The active ones force your core muscles into greater range of motion than when you are riding. This is what allows you to build supple strength along the full length of the muscle, whereas just riding causes your body to strengthen in short segments; under pressure, these become knots. Isometric exercises require you to hold a position for a period of time, stimulating your body to integrate all layers of core stabilizing muscles. You need to train both movement and isometric capacity in your muscles because when riding you need to both hold your posture for a long period of time and change position on purpose and in the moment when you want to.

3. Train endurance. As noted above, you need endurance. Thirty crunches on a ball or your floor are more useful training for a rider than a set of 10 to 15 repetitions using an abdominal crunch machine at the gym with weights. You do not need to use your core to powerlift, just support your own body against constant pressure (the horse’s movement) for an extended period of time. Building endurance in muscles is about more than just repetitions. It takes time to change the muscle fibres so that they are capable of greater endurance.

4. Train eccentric and concentric motion. This means training through both the “up” and “down” phases of an exercise. Resisting motion is just as valuable for strength training as creating motion; most of what your torso does in the saddle is resist motions so your body doesn’t block your horse’s movement and so that it can apply only those motions you need to give aids to your horse. An example of eccentric and concentric training is doing leg rising then lowering on the floor. Most people think of the leg raise part only. Lowering your legs slowly while keeping a neutral spine on the floor actually builds your lower back and abdominal strength more than the lift phase does.

5. Train all four sides and rotational movement. Select exercises that train your abdominals, back muscles, and obliques, and also train rotational movements.

6. Train the full length of your back and abdominal muscles. Select exercises to cover lower, middle, and upper back and abs.

7. When you get more advanced in your core training, mix it up for variety and “layer” your exercises for maximum effect. The same workout will not work for you the same way forever. Having a mix of seated, exercise ball, lying, and standing type core exercises gives you more ways to train a muscle or movement without getting bored. Standing exercises have the added advantage of also giving you a bonus workout to your thighs, glutes, and hip stabilizers. Layering your exercises is where you do one after the other to give the muscles maximum workout by using them similarly but differently back to back. An example would be doing a plank after some crunches on your ball. You will find you do not need to hold the plank as long to get the same burning effect on your deep core muscles and lower back, so you get to save time. For a serious core workout, I would recommend a workout of approximately five to ten exercises with a total of 300 repetitions and isometric exercises sprinkled in between others.

There is a lot more that could be discussed about core training for riders, but to help you get the ball rolling on your own core training, I have included a short core workout that has a structure that is good for riders and covers all six of the above principles. These exercises will cover the basics above and will take you less than ten minutes. If exercises cause pain or strain, stop doing them and consult a healthcare professional.

Exercise #1 - Ball Pass

Area trained: entire length of abdominals

Number of repetitions: 10 to 20

Key: Keep your spine “neutral” on the floor as you lower the ball between your feet. Bend your knees on the way down if you cannot keep your back pressing on the floor. In the up phase, reach the ball up as high as possible towards the ceiling to make your body give 100 percent effort to your abdominal contraction.

Ball Pass #2

Ball Pass #3

Ball Pass #4

Ball Pass #5

Exercise #2 - Side Planks

Area trained: entire torso, especially obliques

Number of repetitions: hold 30 to 60 seconds on each side

Key: It is easier on your shoulders to lean on an elbow on the floor. An advanced version could be up on one hand while doing a simultaneous side leg raise.

Exercise #3 - Back Extensions

Area trained: entire length of back plus rotation

Number of repetitions: 15 to 20 with arms out and the same with rotations on both sides

Key: Raise your body no higher than 45 degrees to the floor to protect your lower back from strain. A simpler version would be lying stretched out on the floor to do the exercise. The ball forces you to keep your hips stable while your shoulders are turning, which is very useful for a rider.

Back Extension #2

Back Extension Side View

Back Extension with Rotation

To read more by Heather Sansom on this site, click here.

All photos courtesy of Heather Sansom.