This article originally appeared April 2013

By Teresa van Bryce

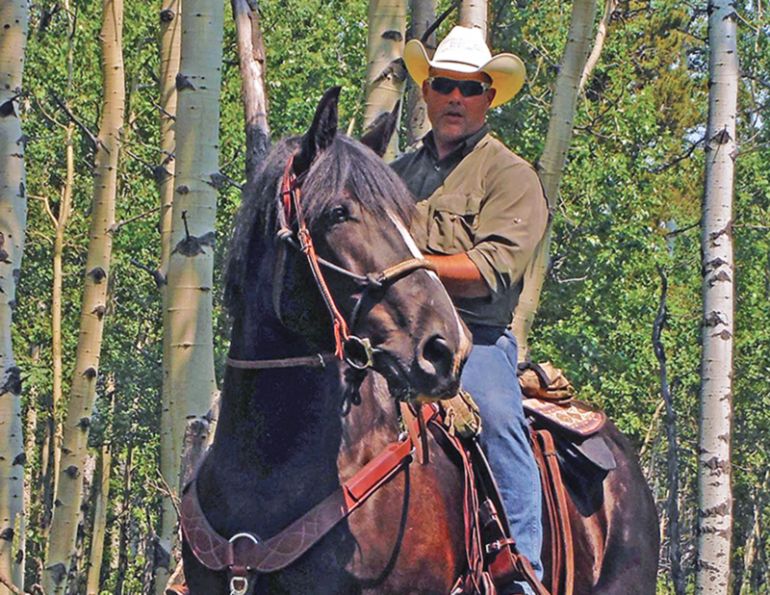

A professor of Animal Sciences at Colorado State University, Dr. Temple Grandin is a world famous expert in animal behaviour and livestock handling. While renowned for her innovations in the design of handling facilities and improving animal welfare in the livestock industry, Dr. Grandin is perhaps best known for overcoming her personal struggles with autism. She continues to teach and pursue her research while lecturing around the world on autism and livestock handling.

Teresa van Bryce: What would you say are the most common misconceptions owners have about their horses’ behaviour?

Dr. Grandin: The most common mistake that’s made in behaviour with any animal is mixing up fear and aggression. Fear and aggression are two different emotional systems. You don’t want to be punishing fear. The other thing about animal behaviour is that the horse doesn’t have language, so the only way it’s going to store memories of good or bad things is a picture, a smell, a touch, a feeling, or something it hears. They make associations with something they were seeing or hearing right when something bad happened. There’s a horse I talk about who is scared to death of black hats. White hats are fine, black hats are bad. It’s sensory based, not word based.

TvB: So when you speak of “thinking in pictures” and animals doing the same, is this what you’re referring to?

Dr. Grandin: If I ask you to think of a church steeple, how does it come into your mind?

TvB: I see it. It’s a picture in my mind.

Dr. Grandin: Now, is it a generalized steeple or a specific one in a specific place?

TvB: Generalized, I would say.

Dr. Grandin: That’s what most people do – generalize. Now, people who tend to be more visual, like me, see specific steeples. This is visual thinking, or bottom-up thinking. I form my concept of what a church steeple is by taking specific pictures and putting them in the church steeple file folder in my brain. There’s no other way an animal can store its memories without verbal language. For example, there was a study done where a horse was habituated to the sudden opening of a blue and white umbrella. But being habituated to a blue and white umbrella does not transfer to an orange tarp because it looks completely different. When a horse gets afraid of something, it tends to be fairly specific.

I talked to someone who had a horse that was terrified of long, straight things, like shovel handles. We got to talking about his history and it turned out this horse had been in cross ties, flipped over backward, and a thick lead rope fell right across his chest. It appeared as a long, straight thing to the horse and so he associated long, straight things with hurting. It’s a fear memory.

TvB: So how do we deal with these issues in our horses?

Dr. Grandin: First of all, we want to try to prevent them. Let’s get rid of things like rough training methods. If you have a horse that’s been abused with a wire snaffle bit, he might see all jointed bits as bad. Get rid of the jointed bit and he’ll be fine because now you’re in a different file.

Now, because I can’t get rid of black hats I have to work out how I’m going to desensitize that horse around black hats. My success is going to vary depending on the flightiness of his genetics. A very flighty horse may never be safe around black hats. The problem with fear memories is that there is no erase. You train the brain to suppress the fear but, if the horse is tired or not with his familiar person, it comes back.

There was a horse in California they used in the feed yards. He’d been in a roping accident, and if anything touched him on the rear he’d get very upset. Holstein cattle will lick a horse if he’s standing in the paddock. If this horse had his favourite rider on him when a cow licked him, the rider could calm him down. The feedlot manager made the mistake of letting someone else ride the horse. A Holstein came up and touched his rear and the horse exploded, went into the fence, and broke his leg. You can suppress it but it’s only suppression.

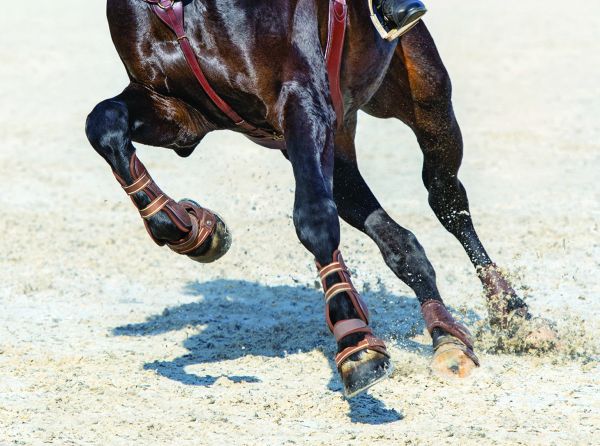

“The horse doesn’t have language,” explains Dr. Grandin. “The only way it’s going to store memories of good or bad things is a picture, a smell, a touch, a feeling, or something it hears…it’s sensory based, not word based.” Photo: Rosalie Winard

I have people say, “My horse is fine at home but we went to a show and he just exploded.” Let’s look at the things we have at a show that you don’t have at home – baby carriages, flags, bikes, balloons. You’d better get him used to that stuff before you go to the show. The best way to teach your horse to tolerate balloons and flags is to decorate his pasture with them and let him voluntarily approach. Don’t take balloons and flags and shove them in his face.

TvB: If work with balloons and flags doesn’t translate to other objects, he’s going to be afraid of something else. So does desensitization help?

Dr. Grandin: Think about it in a visual way. Take an American flag and a Canadian flag. That’s going to transfer, because the way it moves and the approximate shape is the same. But you would need to habituate a horse to pennants because visually they are different than the flag you’d carry for the rodeo parade. Just like the generalizing from the rope to the shovel handle, it’s an approximate shape.

If you want to understand how a horse experiences something, you’ve got to get away from verbal language. You’ve got to start thinking about things visually. Your horse that you’ve habituated to balloons, if he’s only seen single balloons and now is presented with a bunch of balloons, it looks very different.

TvB: When you’re working with horses, there are many different training methods using either positive or negative reinforcement. Which works better in your opinion?

Dr. Grandin: Basically, my approach to animal training is totally positive with one exception – serious aggression. Let’s say I have a horse come at me, teeth bared, full aggression. I’m going to react not very positively. He’s going to run into serious consequences. There’s sometimes a place to use a very severe aversive, once or twice, that’s all. But everything else, when you’re trying to teach an animal how to do a new task, that should always be positive. I think people need to look a lot more into clicker training and things like it. This is the approach you need to be using.

TvB: What if you have an unwanted behaviour in a horse, like pawing?

Dr. Grandin: Make sure you’re not accidentally reinforcing that behaviour. If your horse paws when you go to feed him, don’t put the bucket down when he’s pawing. Wait until he stops and then give him the bucket. Then gradually lengthen the amount of time he has to not paw in order to get the grain.

TvB: And if he paws for half an hour?

Dr. Grandin: I don’t care. He’s not going to get the grain. He doesn’t get the thing he wants until he stops pawing. He stops for a second, you put the grain down. You’ve got to get your timing right. This is one of the advantages of clicker training. You can more easily time the reward stimulus, the click.

Don’t reward bad behaviour. When horses push on you for a treat, they don’t get the treat until they stop pushing. It’s the same with cattle. I get cattle mobbing me at a gate because they want to switch pastures. I’m not going to open the gate until they stop doing it. I might have to stand there for two hours until I open that gate, but having that patience in the beginning pays off. You can usually teach manners by withholding a reward and continuing to extend the amount of time they have to wait.

TvB: Canadian horse slaughter plants have been under fire recently. From your experience designing and auditing humane handling facilities, are the plants in Canada doing a good job?

Dr. Grandin: The plants up here, when I’ve gone to visit them, were fine. But then, when my back was turned, someone got a TV camera in there. The plant in Quebec was using a beef stunning box and the horse could see over the top of the box onto the kill floor. That’s just stupid, and to fix it is simple. Another plant had horses slipping on the floor. Well, put non-slip flooring in there. The other thing you have to have for humane slaughter, and when the plants are short-staffed they don’t want to do it, is two people to run the stun box. You don’t need a complicated design, just non-slip flooring, high sides on a well-lit box, and two people to run it.

It doesn’t require fancy equipment to run humanely but it does require management that cares. They ought to be putting video auditing in the slaughter houses. I think they should just put a camera in and stream it out to a web page. Let the public monitor it.

TvB: Has the closure of the slaughter plants in the U.S. impacted equine welfare?

Dr. Grandin: In the U.S. we have terrible problems – neglected horses, rescues overflowing. The problem is that half the horse industry really objects to the idea of eating them, but nobody has any practical solutions. We’ve got 2000 horses a week going to Mexico. Half of these may be going to fairly decent export approved abattoirs but the other half are going to local abattoirs and being killed by punctilla, which is stabbing the horse in the back of the neck.

I asked activist groups to give me some alternatives to slaughter that I would present to a horse summit two years ago, things like bigger rescue places, euthanasia stations, dude ranches, etc. I presented these things and haven’t had one of them follow up with me as to whether or not any of these things were done. They don’t have a practical solution to the problem. I think that horse slaughter in a decent plant is a better alternative to starving. The problem on these issues is that people are so far away from the practical realities of things.

Main photo: Rosalie Winard - Dr. Temple Grandin is renowned for her innovations in livestock handling and overcoming her personal struggles with autism.