Pit Ponies and Horses

By Margaret Evans

The human race has long had a love affair with coal. Coal is a fossil fuel that started forming in the Carboniferous Period 359 million to 299 million years ago during the Paleozoic Era.

Stone and Bronze Age flint axes have been found embedded in coal, evidence that people were using it for fuel long before the Roman invasion. In the 13th century, coal seams were found along shorelines of northern England, and settlers dug them up then followed them inland under cliffs or hills, the earliest beginnings of drift mining. But with the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, coal mining exploded, providing fuel for steam engines, transportation, and home heating.

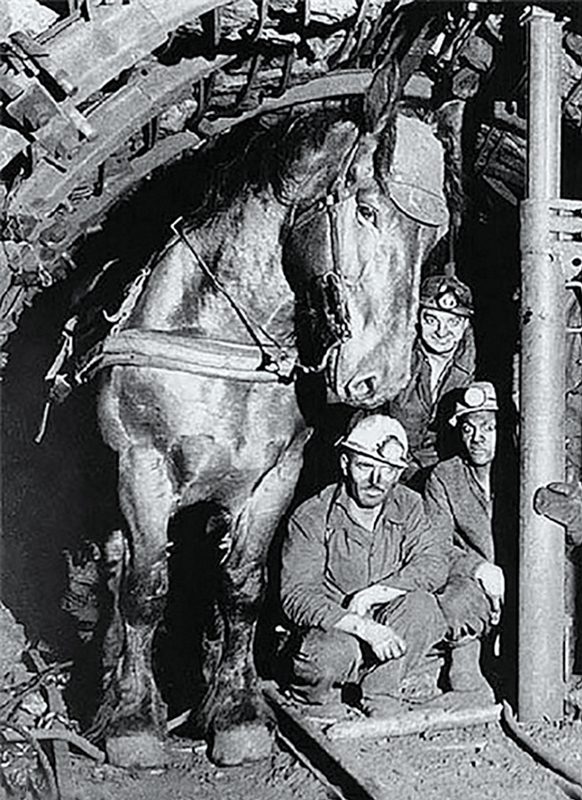

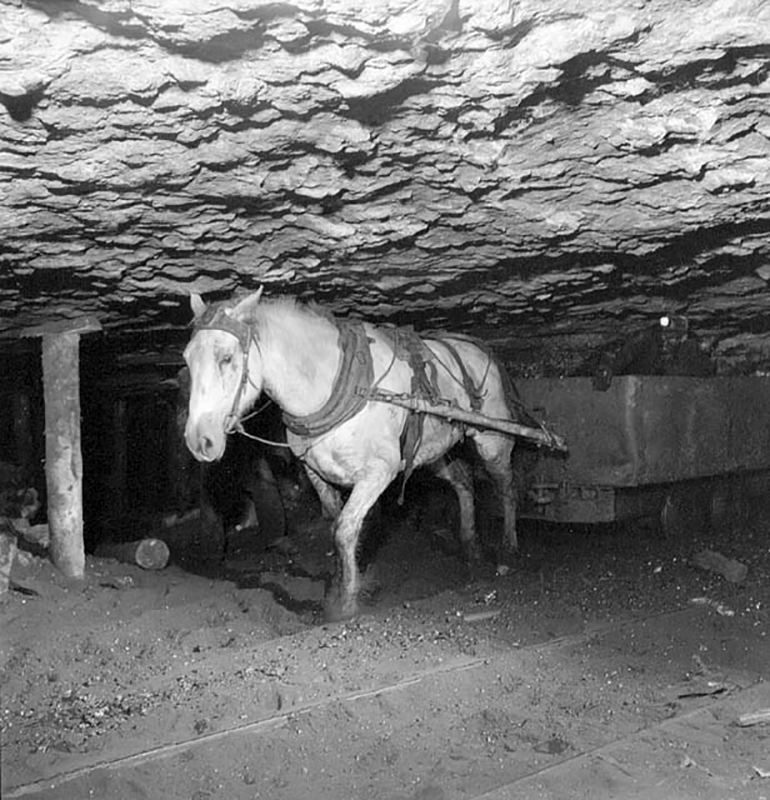

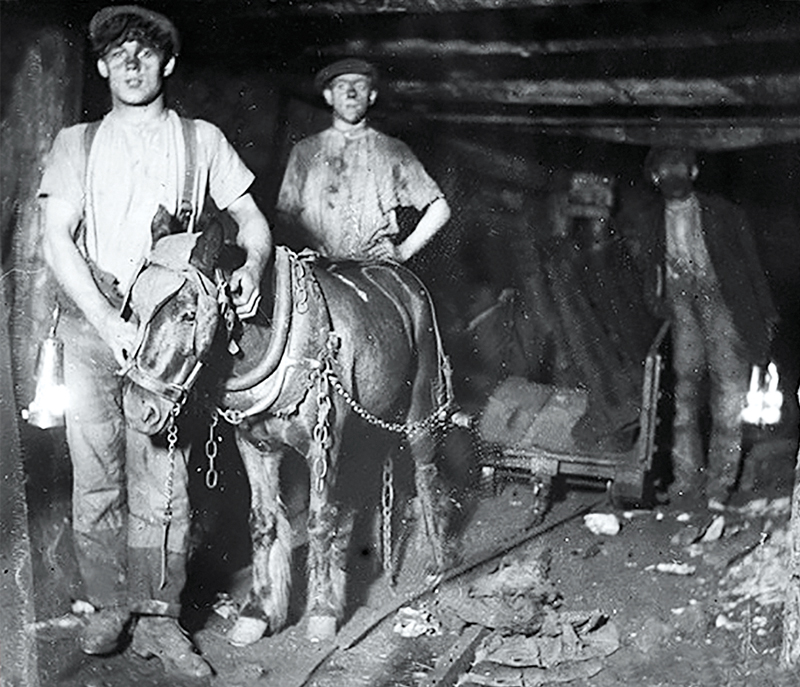

Taller ponies and horses worked thicker coal seams with higher ceilings, and smaller ponies worked the seams with low ceilings.

In the early years, men, women and children worked the mines until laws were enacted to protect females. As productivity improved and underground haulage needs increased, horses and ponies filled the need.

“The first records of ponies being worked in mines was in the north of England around 1750,” says Wendy Priest, Horse Keeper Supervisor at The National Coal Mining Museum for England. “Horses were used on a large scale after the 1842 Mines Act that abolished the underground employment of boys under 10 and all females.

Taller horses would become injured by scraping their heads or backs on the low-ceilinged roadways.

“People who visit the Museum are under the impression that Shetland ponies were mainly used as pit ponies. In fact, all sizes were used, from Shetlands to Shires. In different parts of the country, the width of coal seams varied considerably. Thick coal seams meant high [ceiling] roadways. Large ponies and horses could be found working in these mines. Small ponies such as Welsh ponies and Shetlands [in England] worked in small seams with low tops. Many scraped their heads as they worked as the roadways were so low. Welsh mines commonly used larger Welsh cobs, around 15 hands.”

In ex-miner Ceri Thompson’s book Harnessed: Colliery Horses in Wales, he documents the widespread use of small Shire horses in the main roadways in the mines. Animals larger than ponies were used because the drams held up to a ton and a half of material compared to the smaller half-ton tubs in most English coalfields.

Horses and ponies were integral workers in coal mines, not only in England and Wales, but in Canada and the United States.

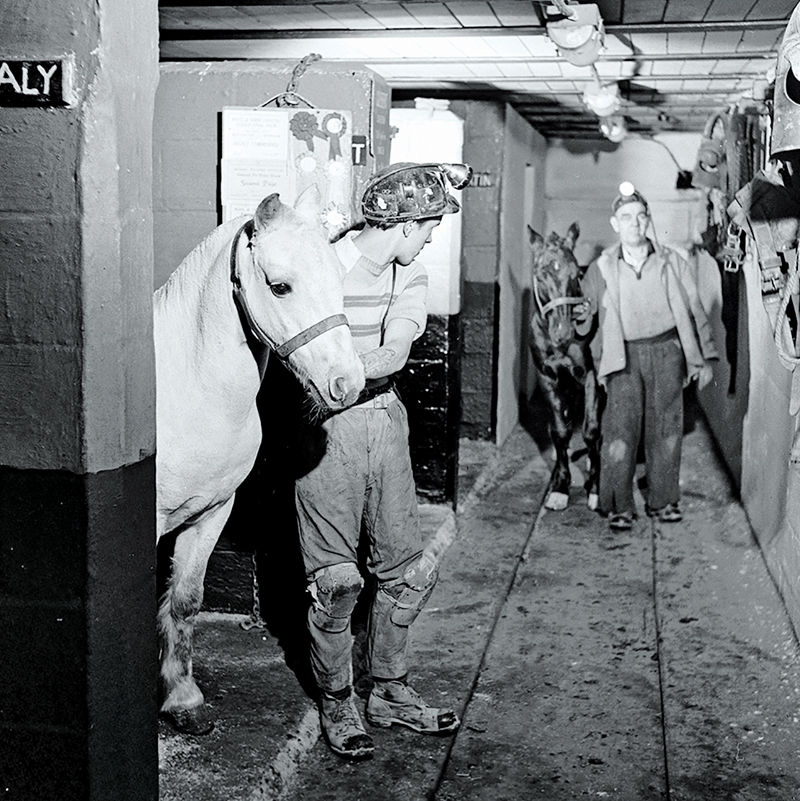

A pit pony and miner in a mine at New Aberdeen, NS, in August 1946. Photo: National Film Board of Canada/Library & Archives Canada/PS-116676

Nova Scotia was the dominant area of the coal industry in Canada, and the earliest coal mines in the late 1700s were on Cape Breton Island and at Pictou in Nova Scotia. On Vancouver Island, coal was systematically mined from the mid-1800s onward. After the arrival of the railroad toward the end of the 1800s, coal was mined in the interior of British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan. Coal is not found in either Ontario or Quebec, the areas destined to become Canada’s industrial heartland.

A paper titled Coal Mining in Canada: A Historical and Comparative Overview written by Delphin Muise of Carleton University and Robert McIntosh of the National Archives of Canada in 1996, describes how horses were introduced for coal haulage in Nova Scotia when increased productivity overtook existing haulage systems.

Related: The RCMP Musical Ride

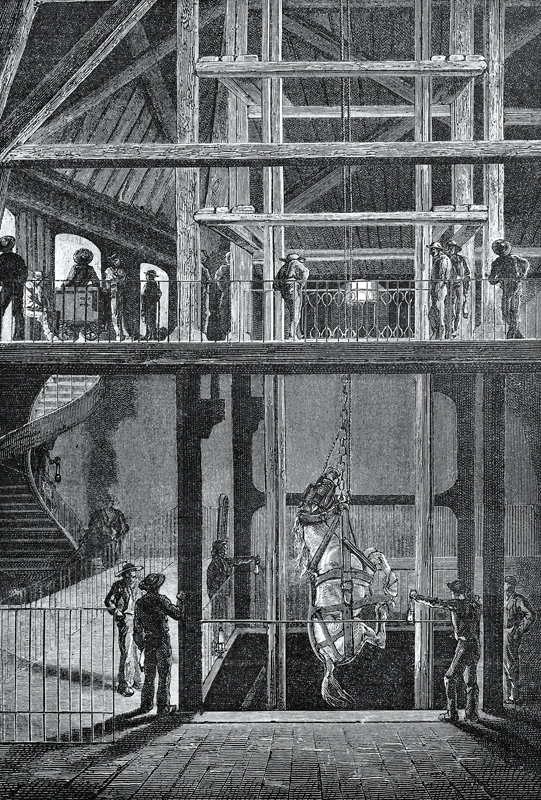

An 1879 illustration of the descent of a horse down a mine shaft. Photo: Thinkstock

“A first step in removing this bottleneck was the introduction of animals to haul coal underground. Horses had been used underground to pull tubs laden with coal in British collieries since the late 18th century. The GMA [General Mining Association], priding itself on adopting the most advanced mining practices, introduced horse haulage underground shortly after its arrival in Nova Scotia.”

At first, they pulled skips, sled-like vehicles pulled over wooden roads made of logs. Gradually the skip was replaced with a wooden coal tub bolted to an iron frame and fitted with a wheeled undercarriage that ran on rails. By 1871, several miles of underground railway were in place on the east coast.

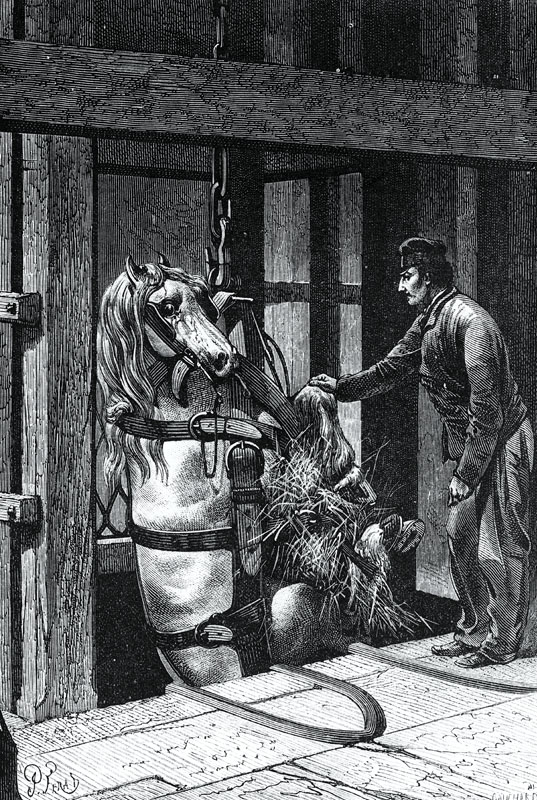

An 1867 illustration of the apparatus used to lower a horse into a coal mine. Photo: Shutterstock/Marzolino

Underground haulage improvements were also made in British Columbia where, in 1856, underground passageways were enlarged to allow the use of horses and mules to haul coal along the levels to the pit-bottom.

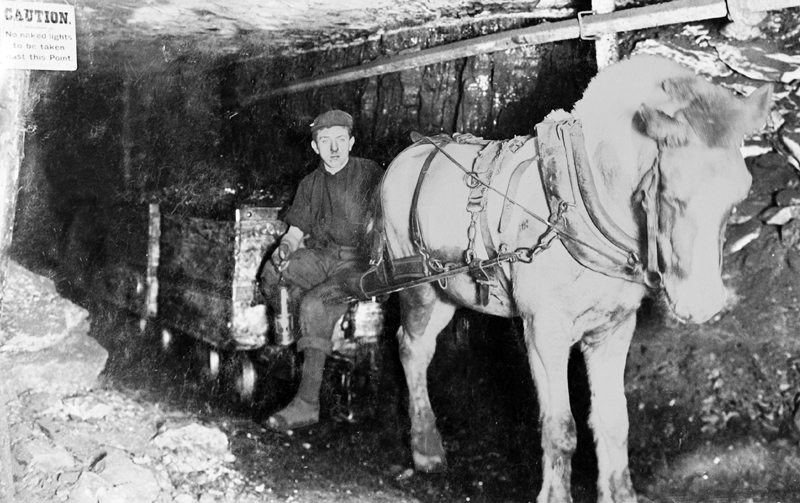

“Driving a horse through the intricate tunnels underground required both finesse and strength,” wrote Muise and McIntosh in their report. “It was often the second job adolescent boys had underground, considered a learning experience that exposed young miners-to-be to the different environments of the mine. Perched between the horse and the tub or tubs being pulled, often with ‘his foot against the horse’s rump to hold back the tub[s],’ a driver led the horse along dark underground travelling roads, collecting tubs loaded with freshly cut coal and transporting them to a point where they could be hoisted to the surface. He then had to return the empty tubs to the working places. The driver’s role was critical to efficient mining. Since a miner’s earnings depended on his productivity, the efficient movement of coal to the surface for processing was essential; empty boxes had to be ready when he was ready to load the coal, and coal had to be delivered to the pit-bottom with a minimum delay and loss.”

In Cape Breton, many ponies were actually small horses from Sable Island shipped to the mainland. They spent their lives underground and it was not until the early 1960s when the last of the Cape Breton pit ponies retired.

A horse bound and ready to be lowered into the mine.

In 1982, Ronald Caplan’s Cape Breton’s Magazine published an article Horses in the Coal Mines that featured interviews with miners who recalled the working conditions for the horses and the dire circumstances they sometimes faced.

Miners spoke of horses scraping the tops of their heads on the ceiling so that flesh would be hanging and bone exposed. In really low tunnels they would get jammed by their withers. Injuries often got infected in the dirty air and required veterinary treatment, or more drastic treatments such as the use of syringed kerosene oil which seemed to absorb pus and discharge. Occasionally a horse would pick up a bacterial infection leading to tetanus. Horses used in the mines were either cured of an illness or injury, or euthanized in the event of a catastrophic injury like a broken leg. Any horses that were unwanted or unsuitable would be offered to local residents, who were always a willing market.

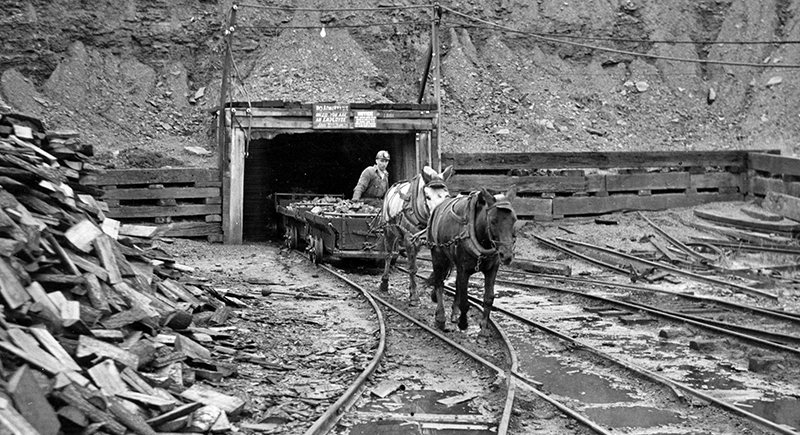

Horses hauling loaded coal wagons to the surface at Drumheller’s Newcastle Mine in the 1920s. Photo: Provincial Archives of Alberta, A6152

It was exhausting, filthy work. Several dozen horses were used in a mine and the underground roads had to be kept clear of pit water which, in Cape Breton’s submarine mines, was acidic and salty. Standing water not only interfered with the movement of coal tubs but aggravated cuts on the horses’ fetlocks, causing inflammation and infection.

Related: Horse Hooves in History

While treatment of the ponies varied from mine to mine, they were adequately cared for since operators understood that their working efficiency was directly related to their animals’ health. There was further incentive given the cost and time involved in purchasing and training a replacement for an injured or sick pony. Many miners lamented that management was more concerned with the ponies’ care and safety than with the men since “you could replace a man anytime them days.”

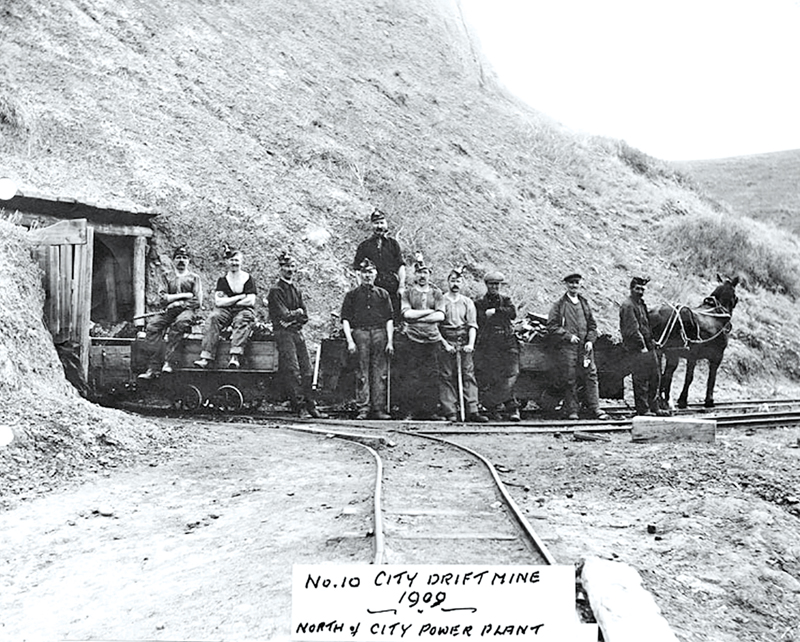

A drift mine owned and operated by the City of Lethbridge in 1909.

Some mines had underground stables where the horses and ponies were housed for most of the year. They were brought to the surface and turned out to pasture when work slowed down. A stableman was in charge of the underground stalls and it was his responsibility to make sure there was a good supply of feed and water for the animals. Other mines would transport the ponies up and down in shifts much like the miners themselves.

The Horses in the Coal Mines article reports that, in the early years, many horses in Nova Scotia mines went underground and stayed there year in and year out. But that changed in the 1940s when miners started getting vacations and horses were brought up for their own vacation and turned out in a large field. Understandably, they loved it and would gallop around the field kicking and bucking. Their eyesight needed to adjust to the brightness of daylight, and puddles they’d normally step through would be jumped as obstacles.

In Pennsylvania, some of the oldest mines used oxen, then mules, to pull the coal cars in and out of the mines. Mules were preferred over electric mine motors and were used right up to the mid-1950s when many mines were shut down. Motors ran on an overhead electric trolley line and, in the presence of even a small gas problem, a spark could trigger an explosion – using mules avoided that hazard. The mules were smart, hard-working, and they could pull at least three full mine cars of coal.

Operations at the Humberstone Mine in 1918. In this year it was reported in the Edmonton Journal that the mine was the best equipped in the Clover Bar field, with a capacity of 1,000 tons per day. Photo: City of Edmonton Archives

In Alberta in the late 1800s, ponies, mules, and horses were put to work in the coal mines. One mine might have as many as 80 ponies that were capable of pulling five fully-loaded coal cars. Like miners elsewhere, Alberta coal miners developed a fond relationship with their animals, often bragging about how smart they were, or how strong, or how heroic. Working with the same animal, a miner forged a bond with their pony and each got to know the other and how they worked together.

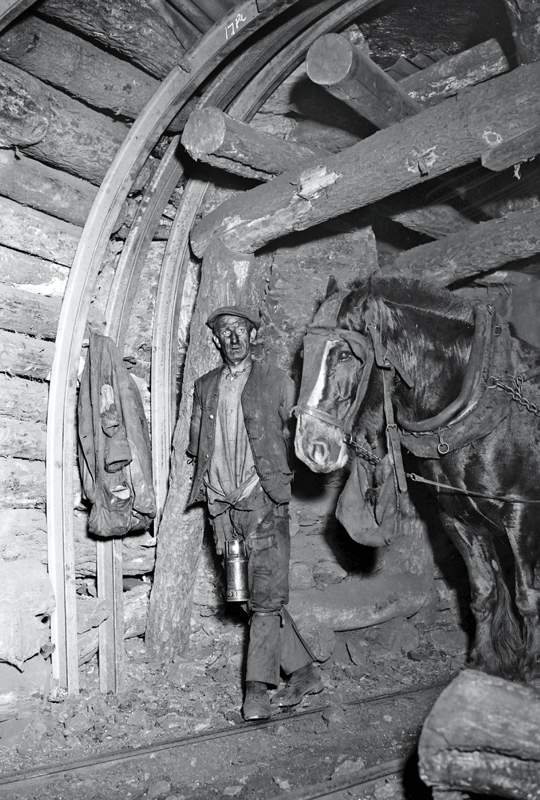

Pit ponies worked in mines at different depths. In England, deep mine ponies lived underground from depths of 125 metres to over 150 metres. Retired miner Tony Banks, a pony driver, worked in The Manor coal mine at a depth of 247 metres. The deepest pits in Wales went down 700 metres.

Miners often took two packs of lunch or ‘snap,’ one for the pony and one for himself.

“I used to have a pony called Ted,” says Banks. “He was a great pony to drive. I used to give him a nice brush down before we left the stable before I fitted his collar and mobs. Then the next job was his nose bag for snap [lunch] time. He would get a mint or spangle [a boiled candy] just before we set off on our way. I used to whistle on my way up to his stall and he knew it was me. It was a sad time when I had to give him up when I went coal face training.”

Ventilation and the provision of quality air was essential and was done with intake and outflow pipes from the surface. Air going in and air going out had to be kept separate, which was done with air doors to maintain air quality in each area of the mine. Air doors prevented leakage of intake and return air, and they had to be kept closed. Before ponies were used in the mines, it was the job of children eight years of age and younger to sit in the dark and open and close the doors when the coal drams passed through.

This photo of “Little Tick,” a favourite pit pony, was taken in England in 1913.

Pit ponies and horses developed unique skills. They learned how to turn around in small spaces, respond to verbal commands, and open the ventilation doors. They worked in total darkness but knew their way around.

A new boy could expect to start his career as a pony driver. He would be given a pony and told to harness it up in its stable and take it to the workings. Priest says that, at some point, the boy would need to let go of his pony and that would be the pony’s cue to bolt to his stable maybe three miles away along pitch black roadways, along the way pushing the air doors open with its head gear. They were savvy and mentally sharp, developing other instincts where their eyesight would be challenged in the darkness. Ponies rendered blind in one eye from injury would learn to rub their noses against hard stones to feel their way as to where to turn.

In a typical working day of eight to twelve hours, a pit pony would regularly pull out 30 tonnes of coal.

Related: The Heritage and Skill of Riding Sidesaddle

A mine portal with horses at the S.C. Streams Black Diamond Mine, Creekside, Indiana County, Pennsylvania.

Priest says the ponies could count. “When working, ponies pulled drams or tubs of coal. These tubs were on rails a little like railway carriages. Ponies could actually count! I have been told this hundreds of times by ex-miners. They listened for the click as each tub was attached. Three was acceptable, four was not. The pony would not move until the fourth was taken off.”

She recalls how the ponies saved lives. “Ponies often stopped in their tracks, refusing to move. The next minute, the roof [ahead of them] has fallen in. Ponies saved the lives of many miners this way.”

A group of coal miners with their horses used to pull coal carts at Hillcrest, Alberta, in 1920. Photo: Library and Archives Canada/PA-1

And those ponies were smart. “There were some ponies that actually got on the conveyer belt with the miners and had a ‘ride’ back to the stables.”

The mules in the Pennsylvania mines had the same instinct to count the number of cars being hooked with chains. Three was okay with them. But they wouldn’t pull a fourth. Mule drivers figured the mules were counting so when they wanted to hitch a fourth they would do it quietly and discreetly and the mules would pull that extra car unknowingly.

Wendy Priest of The National Coal Mining Museum for England, introduces the museum’s horses to Princess Anne when she came to open their new underground education classrooms and extended tour section. Photo courtesy of The National Coal Mining Museum for England

Horses also demonstrated that counting ability. Phil Budding worked in a small mine and he told Ceri Thompson of the savvy nature of horses.

“Every day they would pull their drams out of the pit and, after they had been disconnected, they would turn and go back into the mine. After they had pulled eight drams out, they would head for the stables instead of going back underground. On the weekend, we’d only have to do six drams and, after they had disconnected them from the sixth dram, they’d turn and go to the stables. On the Monday, they would again wait for the eighth dram before heading for the stables. They could not only count, they also knew what day it was. They were clever horses, they were unbelievable.”

In the 1870s, there were an estimated 200,000 pit ponies in Great Britain. Life for these animals was very hard, many working up to 16 hours a day, often without food or water. Some animals never saw the light of day. There were widespread reports of abuse, injuries, and sickness.

A Welsh miner and pit pony partner. Photo courtesy Big Pit National Coal Museum, Blaenafon, Wales

In 1876, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) campaigned for the protection of pit ponies and urged the government to consider the suffering of the animals hidden from view, deep underground in coal mines. In 1914 the RSPCA reported that of 70,396 horses and ponies working in British mines, 2,999 suffered injuries resulting in death, while 10,878 were injured but survived. Not included in these numbers were the ones that had to be put down due to old age.

Related: History of the Draft Horse: The Muscle-Men of the Horse World

“Blind ponies were not allowed [by law] to work in the mines,” says Priest. “Working in the dark did not make them blind as such. Ponies’ eyes were damaged due to injury from falling rocks or sharp objects hitting them. Old age sometimes caused blindness. They had lung problems with the coal dust, as did the miners. The Coal Mines Regulations Act of 1887 offered the first proper protection for working horses and ponies in the form of mine inspectors to monitor how horses and ponies were treated underground to the extent that the roadways should be big enough to allow ponies to walk along without rubbing against the tunnel. The Coal Mines Act of 1911 was more effective and the section dealing with ponies became the ‘Pit Ponies’ Charter.’”

A Welsh miner and horse. Note the miner’s lamp hanging from his belt. Photo courtesy Big Pit National Coal Museum, Blaenafon, Wales

The Charter overhauled the management of pit ponies with instructions on their use and care, working hours and shifts, a minimum age of four before working underground, annual veterinary checks, and provision of adequately sized stalls with clean straw or other suitable bedding. All stalls had to be cleaned daily and kept sanitary. Further acts of 1949 and 1956 built on these mandatory conditions ensuring further protective care.

Miners who looked after ponies underground were known as Horse Keepers. In south Wales, they were known as “Gaffer Hallier.” They were responsible for the care of horses, ponies, harness, and tack. Where possible, stables were constructed in an area where clean fresh air could be fed to ventilate the stables and take the smell of urine and manure out by way of the return airway. Manure waste had to be transported out of the mine. Feed had to be brought in and all feeding requirements had to be met day and night. An ongoing problem was the number of rats and mice that were always getting into the animals’ feed supply.

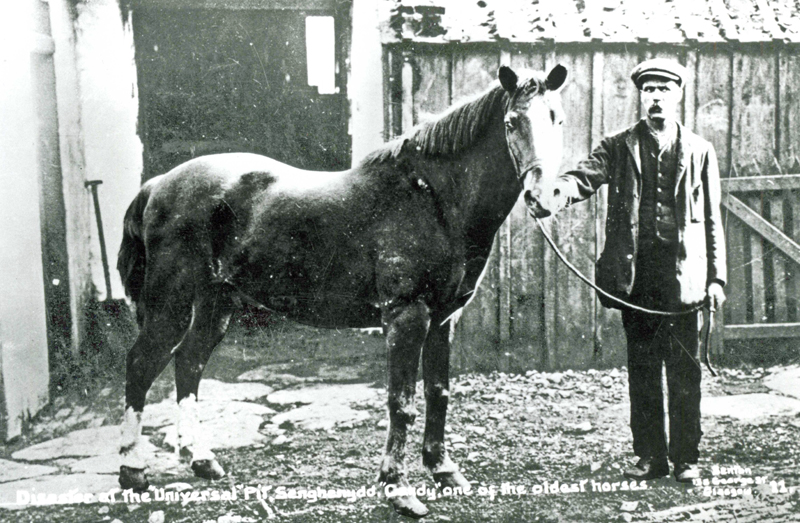

This historic photo was taken on the surface of the Universal Colliery, Senghenydd, Wales, during rescue attempts after the biggest mine explosion in the United Kingdom that occurred on October 14, 1913. It killed 439 miners of the estimated 1,000 who were underground at the time, plus a rescuer. There were up to 200 horses underground at the time, and at least 100 were killed. The likely cause was a build-up of firedamp ignited by an electric spark. The Senghenydd explosion was the worst coal mining disaster in British history. The site has now been cleared and a garden has been created as the Welsh National Disaster Memorial. Photo courtesy Big Pit National Coal Museum, Blaenafon, Wales

Because the horses and ponies worked hard in a warm, sweaty environment, their coats, manes and tail hairs were totally clipped off, a practice that began at least as early as 1890. This made cleaning them after a shift simple. They were hosed down or taken through a bath to wash away the coal dust. Clipping minimized sweating, which allowed them to cool down more efficiently.

Priest says that, understandably, ponies going underground for the first time would have found their new life very alien. And it started with transporting them down the mine on a cage. Larger horses that could not fit on the cage had all four legs bound in straps and were lowered down on a cable under the cage.

“This must have been terrifying for them,” says Priest. “Some would have had training, some would not. Fear and panic must have been commonplace. Injuries were many, such as falling, scraping their heads or backs on the low roadways, being slammed into air doors when braking systems in the wheels of their drams [carts] failed, and falling rocks and roof falls. There were miners who were good to their ponies and there were some who were not. The pressure was on the men to get coal out fast. Some ponies would have settled into their roles easier than others. Many died, many went on to work for years.”

Related: Remarkable Horses in Canada: Big Ben

Robbie was the last horse working in the mines in Wales. He retired in 1999 from Pant-y-Gaseg Mine which, in translation, means “Horse’s Hollow.” Photo courtesy Big Pit National Coal Museum, Blaenafon, Wales

Priest says that a pit pony’s first set of shoes would have been fitted above ground before its descent into the mine. Templates were made and kept for each pony so that subsequent sets of shoes could be fitted cold underground. Sparks from hot shoeing could cause explosions.

When ponies began their mining life, some mines invested in a short training course so that the animals could get used to wearing harness and pulling carts on rails. This also allowed them to identify any ponies that would not be suitable for the work.

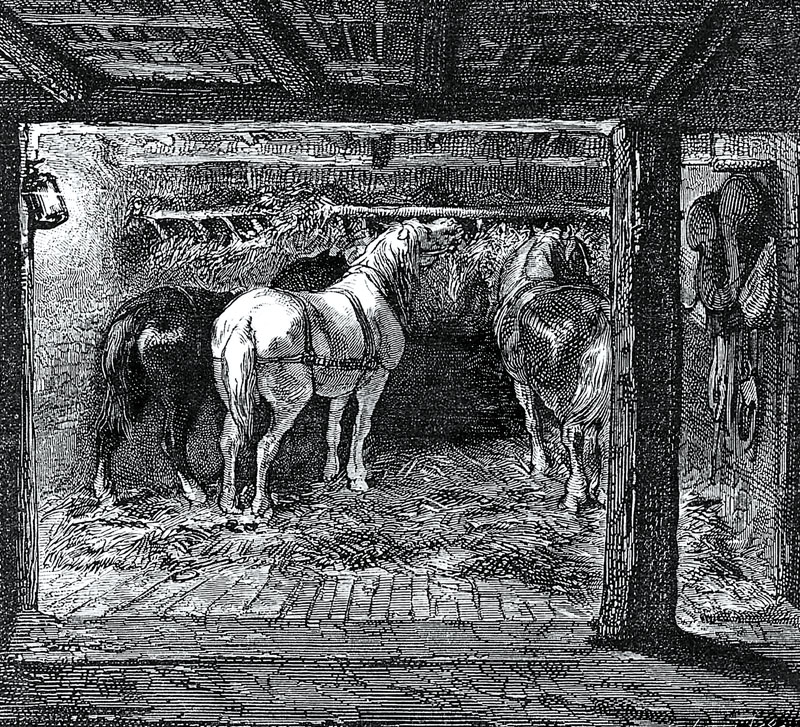

An 1879 artist’s depiction of a stable inside a mine. Photo: Wikipedia/Public Domain

The overman Horse Keeper was responsible for dealing with injuries and would report sick or injured animals to the veterinary surgeon who had the authority to stop them from working.

Accidents were numerous. Thompson, Curator of Coal Mining Collections at Big Pit National Coal Museum, Blaenavon, Wales, has gathered many anecdotal stories of horse incidents.

The underground stables showing ponies with manes clipped off, and the harness hanging including a protective bridle. Note the ribbons hanging in the white pony’s stall. Photos courtesy of The National Coal Mining Museum for England

“We had a horse that used to play up [be disobedient],” Reg Griffiths of Big Pit Colliery told Thompson. “On the third week, I was leading him when he bolted. I had hold of the harness and was trying to pull the stop wire to stop the haulage engine because it was pulling a journey [train] of drams up the heading towards us. Unfortunately, the horse broke free and I couldn’t stop the engine in time. He ran smack into the journey and was killed. The under-manager came in and said, ‘Pity about the horse’ – he wasn’t worried about me – ‘Make sure you save the tack.’ The dead horse was lifted up into an empty dram with his legs sticking up in the air and sent up the pit.”

Ceri Thompson writes of an incident told to him by a retired miner in which one horse was severely injured and screaming in pain and fear. The retired miner says, “He was cut very badly and his ribs were probably smashed. He was squealing with pain, an awful noise I will never forget. It was heartbreaking. I was told to run and get a shot firing battery, a length of shot wire, and a detonator. The detonator was pushed into the horse’s ear and fired, killing the horse instantly. I don’t think that was at all legal but you couldn’t let a horse suffer like that. Everyone involved was in tears.”

Budding also lost a horse to an accident. “That was Sam. He lost his footing on an incline and broke his back. We had to have the vet there and the Mines Inspectorate. There was an almighty row about it all. Horses in mines had more consideration paid to them than the colliers [miners].”

Related: To Serve and Protect: The Death of Brigadier

There were an estimated 200,000 pit ponies in Great Britain in the 1870s. Photo courtesy of The National Coal Mining Museum for England

Horses and ponies working drift mines had life a little easier. These mines had horizontal seams of coal at the surface so the animals hauling tubs, or drams, would move in and out of the mine. They would be turned out in a field at night or left with food to roam the yard until the next day.

Priest says that many miners formed strong bonds with their ponies. “Miners often took two packs of ‘snap’ each day, one each for the miner and his pony. One of our guides at the Museum, who was a horse keeper in the mines, can remember one miner’s wife making carrot cake - a rather large one – to cut up for the pit ponies at Christmas.”

But, she adds, there were men who were not nice to the ponies and this caused friction, even fighting, among the men. Miners had to see their beloved ponies sometimes work for other miners who had no respect for the animals and often had no working knowledge of them. This frequently meant that the good, willing ponies were worked both shifts as men coming on shift would go for the easy animals first. Then there were those who were downright cruel. To these hardened miners, ponies were just a machine for moving coal.

Museum guide John Dransfield and Eric in an original pit harness worn underground at Ellington Colliery by Carl, a pit pony that spent his retirement with The National Coal Mining Museum for England. Photos courtesy of The National Coal Mining Museum for England

Thompson wrote of one incident recounted to him by Raymond Goodwin, Bersham Colliery.

“I’ve seen men wallop the horses with pieces of timber, but if you’re going to work with horses you might as well be nice to them,” Goodwin says. “Because they’ve got a mind of their own they’ll try and get their own back otherwise. We had a new fireman [colliery official] who was a nasty bugger. This chap lost his temper with a horse and shouted, ‘Get out you devil!’ And the horse ran, didn’t it? He sent someone to look for the horse and he ran around like a fool trying to find him. I think that he nearly got to pit bottom. But there was a little side road just off the heading we were working in where there was a tub and some horse feed and the horse was in there hiding in the dark. I think that it was the horse’s way of paying the fireman back for being nasty to him. It’s marvellous to think that he had no light but the horse could sense his way around the labyrinths of roads underground.”

In England and Wales some of the pit ponies came to the surface for an annual two-week pit holiday. They would be brought up on the cage with sacks over their eyes to shield them from the sudden light.

John Carrington (right) was a horse keeper down the mines. He is pictured with guide Bob White and Finn, the museum’s Clydesdale. Photos courtesy of The National Coal Mining Museum for England

“During the Pit holidays, I used to call in the pit field to see Ted,” says Banks. “I would call out his name and he would trot over to me for an apple or a carrot and a good stroke on his neck, and he knew I would have a mint or a spangle in my pocket for him.”

“There are no horses or ponies working in British mines today,” says Priest. “The last deep mine ponies came out of Ellington Colliery in 1994. Two of them, Carl and Sparky, came to us at the Museum to live out their retirement. In Wales, there were a number of privately owned drift mines that continued to use horses and ponies as this was a cheaper means of getting coal out compared with the cost of mechanized haulage. The last two horses came out of Welsh drift mines in 1999. They too, came to the Museum to retire. Patch and Robbie were still relatively young so they were trained for riding and driving at the Museum as it was felt that they would benefit from the stimulation. They did well with us. Patch even went on to become a bit of a celebrity, appearing in the pageant commemorating Queen Elizabeth’s Golden Jubilee in 2002. He pulled a dray loaded with sacks of coal. There were around 1,000 horses in the production. Carl the pit pony also starred, all dressed up in his pit gear.”

Related: Unhorsed: Dismounting Anti-Black Racism in Horse Racing

A better life! Carl (grey) and Sparky, retired pit ponies from Ellington Colliery, lived out their retirement at the museum. Carl, one of the last pit ponies to come out of a British mine, came to the surface in 1994. Ellington Colliery was actually under the North Sea as well as underground.

In one of the world’s most hostile and dangerous working environments, men and their horses and ponies were challenged every day to remove the coal. It was hard, dirty, hazardous work that came with the constant danger of injury or death from falling objects, equipment failures, and roof collapse, as well as occupational health hazards including black lung disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension, and cancer. Yet many miners were very kind to their ponies and depended on them implicitly. They were, after all, their means to their only livelihood. Priest says that while many didn’t think the mines were the right place for horses and ponies, they were glad they were down there with them as the pit ponies were their workmates and they always remembered them with fondness.

Their significance to the workers was profound and reflected in many poignant ways. Thompson recalled an incident told by a small mine owner in West Glamorgan that perhaps epitomizes the miner-equine relationship. A horse was killed in his colliery. As it was pulled out in a dram, all the shift workers stood in a line with their helmets off in respect, and sang a sad Welsh hymn as he passed by.

Pit Pony Lamp and Bridle

This is a pit bridle from Welsh drift mine and old miner’s lamp.

Often, the tack used at mines was made of whatever resources were at hand. Many of the deep mine pony bridles were made of leather with metal eye pieces for protection. There were different designs in different pits. The material used was often rubber conveyor belting held together with rivets. There was no bit. Eye injuries were common until effective protective headgear with eye guards was made compulsory in the early 20th century.

Pit lamps were used throughout the entire era of coal mining. In some mines, lamps were fitted on the pit ponies’ bridles. Some mines had electric, sealed lights at the pit bottom and in the stables. The only light on the roadways came from the cap lamps the miners wore. The roadways to the workings were pitch black with no light at all yet the ponies could easily navigate their way back to the stables.

The electric lights were sealed so that gas could not get in and cause an explosion. Miners relied on their cap lamps and gas lamps as they worked.

Before safety lamps were invented, miners used candles with open flames, which caused frequent explosions. These were also used for detecting gas in the mines. Many harmful gases or “damps” were produced during mining operations. Firedamp, which occurs naturally in coal seams, is nearly always methane, and is highly flammable and explosive. Carbon monoxide (white damp) is particularly toxic, and as little as 0.1 percent can cause death. An excess of carbon dioxide and nitrogen in the air (black damp) is an atmosphere in which a flame lamp will not burn. Stinkdamp refers to hydrogen sulfide, characterized by a rotten egg smell. The gas mixture found in a mine after a fire or explosion is called afterdamp.

Since 1911, canaries were used in mines to detect possible carbon monoxide. Signs of the bird’s distress were the first indicators of a problem. Their use was phased out in 1986.

Related: A Country Built by Horse Power

Related: Forged in Fire - When Horses Answered The Alarm

We extend a very special thank-you to Wendy Priest, Horse Keeper Supervisor at The National Coal Mining Museum for England, for the information and photos she provided about pit ponies in coal mines in England. Thanks also to Imogen Holmes-Roe, Curator of Art and Photography, National Coal Mining for England, for sourcing historic photographs.

We also extend grateful thanks to Ceri Thompson, Curator of Coal Mining Collections at Big Pit National Coal Museum, Blaenafon, Wales.

The era of the pit pony is not yet over. Today, in the Chakwal District of Pakistan, thousands of donkeys still toil in the coal mines where they work the coal seams inside the Salt Range Mountains. Rather than being hitched to coal cars, the donkeys carry heavy sacks of coal out through narrow tunnels. It is hard, hazardous work.

Brooke is the only animal welfare charity with a presence at any of these mines. Their veterinarians are treating the animals and working with mine owners and laborers to improve working and living conditions for the animals. Photos: Freya Dowson/Brooke