Rotational grazing can help you take better care of your pastures and provide more feed for your horses.

By Laura Kenny, Extension Educator, Equine

Most farm managers have heard the term “rotational grazing” but may not fully understand the concept. When used correctly, rotational grazing is a management practice that results in healthy, thick stands of forage to provide horses with a significant source of nutrition. High-quality pasture can meet or exceed the protein and energy requirements of horses with low calorie needs. Rotational grazing requires a bit more oversight than continuous grazing, but the payoff is increased feed value for horses and productive pastures that need less frequent renovation. It is also a good way to manage moderately stocked farms for maximum productivity.

In general, you need two to four acres per horse if you want the horses to be out all the time and not overgraze the pasture. Most farm owners don’t have this much space, but with more intensive grazing management, horses can be maintained on fewer acres and still have great pastures. Of course, even using rotational grazing, there is a limit to the number of horses the land can sustain.

What are the Drawbacks of Continuous Grazing?

Most horse farms practice continuous grazing, in which pastures are occupied by horses daily. There might be one group of horses outside all day, or multiple groups of horses going out in shifts. The important factor is that the pastures are not “rested” or left empty for more than a portion of the day or night. While this is usually the easiest way to manage turnout, it can be very hard on the forage plants and often results in overgrazed pastures on farms with less than two to four acres per horse.

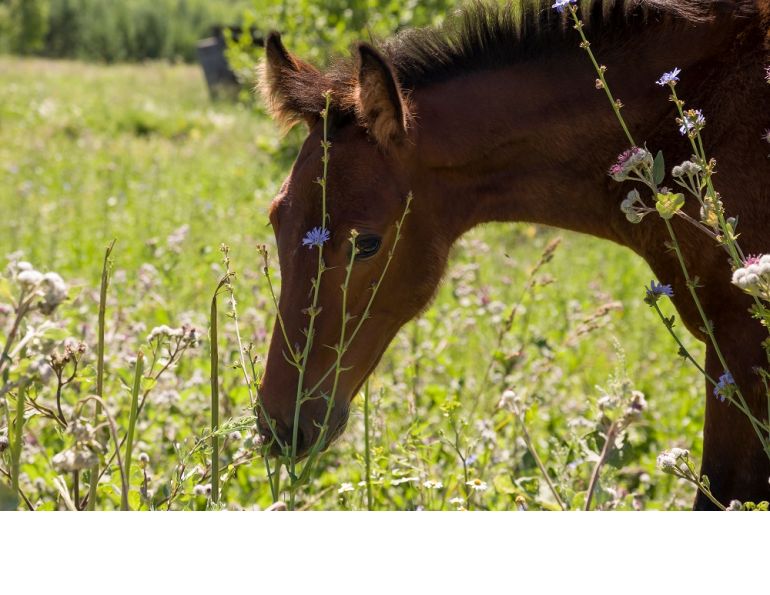

Horses have a tendency to graze their favourite grass species close to the ground, then return to graze the regrowth as soon as it appears. This is overgrazing, which is very damaging to grass plants. First, it removes so much of the leaf area that the plant can’t capture sunlight to make energy for regrowth. The plant must then use stored energy to regrow, and with repeated close grazing, the energy stores run out and the plant dies. This is how pastures lose desirable forage species like orchard grass, smooth brome, and timothy. Horses overgraze these palatable forages until the plants die, leaving less preferred species. As they die, the bare ground left behind allows opportunistic weeds to germinate and take over. You can overseed again and again, but the grazing management won’t allow desired forages to survive except in the ungrazed roughs (areas of taller grass where manure is deposited).

Horses graze the most desirable forages, and then regraze them as soon as regrowth appears. If overgrazed, these desirable plants will die and because nature abhors a vacuum, weeds will germinate and grow on the bare ground. Photo: Pam MacKenzie

Related: Care & Feeding of Overgrazed Pastures

Rotational Grazing

Farm managers can avoid overgrazing pastures by managing their horses’ grazing using a rotational system. In a nutshell, rotational grazing involves moving a group of horses between several paddocks on a regular basis. The forage is grazed once and then rested to regrow. The most important part of this system is the grass’s recovery period while horses are on other paddocks. This means that paddocks must be left empty for a few weeks at a time.

Every farm manager will figure out the right schedule for their rotation, but in general, horses should be in a paddock for no longer than seven days, because that is how long it takes for forage regrowth to begin after grazing.

The Ideal Rotational Grazing System

Photo: iStock/Cringuette

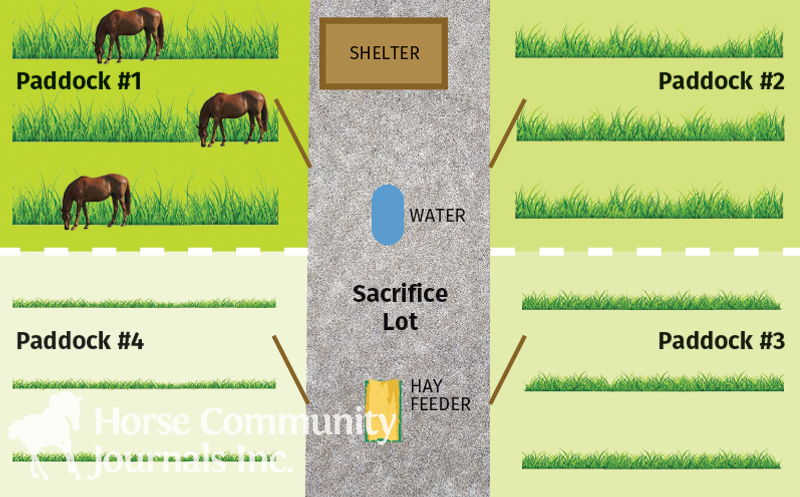

The ideal system has a minimum of four paddocks connected by gates to one sacrifice lot (dry lot, stress lot, animal concentration area, etc.). The sacrifice lot contains a shelter and feeder/water sources so that each paddock doesn’t need to have its own; horses have access to the sacrifice lot at all times no matter which paddock they are grazing. The size of each paddock depends on the number of horses in the group and the overall area available for grazing.

Related: Stream Care Strategies for Your Horse Property

To use this system, the manager starts by walking each paddock and identifying one that is ready to be grazed. It should have at least six to eight inches of forage before grazing. The manager opens the gate to Paddock #1 and closes the gates to all others. The horses graze until they have removed about 50 percent of the forage, leaving three to four inches of forage remaining. This is the take-half-leave-half rule. The grazing period should take no longer than seven days, and forage should not be grazed any lower than three inches. The manager then opens the gate to Paddock #2 (or whichever one is ready to be grazed) and closes the gate to Paddock #1. This continues until horses have grazed all the paddocks.

An ideal rotational grazing system has several grazing paddocks attached to a sacrifice lot. In this example, the horses have access to the paddock with the tallest forage. They just finished grazing the bottom left paddock and will graze the top right paddock next.

If the horses graze each paddock for seven days, each paddock will get three weeks of rest, which should be enough time for forage to regrow to six to eight inches in the springtime. However, in hot summers, cool-season grass growth slows and recovery might take as long as eight weeks. It is important to decide when to graze and move horses based on forage height, not by sticking to a strict timeline.

If no paddocks have recovered by the time all have been grazed, then the horses should be confined to the sacrifice lot and fed hay as needed until a paddock is ready to be grazed. Remember to gradually reacclimatize your horses to pasture when the paddock is ready to avoid colic or laminitis.

Having empty fields for a few weeks makes it easier to take care of some other routine pasture maintenance. For instance, if you need to apply fertilizer or herbicide, you can apply them right after you move horses and rest easy knowing the paddock will be empty for several weeks. A regular schedule also allows you to mow the pasture to a uniform height right after you move horses so that all forage begins its recovery at the same height.

This farm has two totally separate rotational systems, as shown in green and yellow. The yellow system has a sacrifice lot in the middle of the pasture area and adjacent to the driveway, with gates allowing access to the paddocks. The green example shows the sacrifice lot beside the driveway located fairly far from the paddocks (on the right), attached to them by a laneway along the driveway.

Related: To Mow or Not to Mow...? Horse Pastures, Paddocks, and Fields

Common Issues and Solutions

Q: With the cost of fencing, how can I afford rotational grazing?

As long as you have sturdy perimeter fencing, you can subdivide the paddocks using temporary electric fencing. They can be powered by solar chargers. This cuts down on cost and also allows you to move the fence-lines if needed.

This farm used electric rope to divide a larger pasture into strips. The paddock on the left has had more time to rest than the paddock in the middle. Photo: Danielle Smarsh

Q: It has been seven days - why haven’t my horses grazed the forage halfway yet?

Your paddocks are probably too large. If you divided them with temporary fencing, you can move the fence-lines to make them smaller. You could also try adding a horse to the group to increase the grazing pressure.

Rotational grazing pays dividends by making pastures more productive and increasing the forage value. Photo: AdobeStock/Chelle129

Q: My horses aren’t grazing uniformly; some areas are tall and others are low. How do I know when to rotate?

This is normal grazing behaviour for horses, but rotational grazing aims to reduce this pattern and get horses to graze more uniformly. Walk your pasture with a yardstick to get an idea of the average height of the forage. Mow after moving horses. Make sure low areas have grown to the minimum grazing height (six to eight inches) before grazing again. Your pastures also might be too large.

Q: How can I avoid changing my horses’ diet suddenly if I confine them to the sacrifice lot?

Some people keep “summer paddocks" available for this purpose. These are extra paddocks to be grazed when other paddocks are recovering. The extra paddocks will grow very tall if left unmanaged, so they might need to be mowed a few times to keep the weeds down and the grass at a reasonable height until they are ready for use. If you have the equipment, you could even take hay off this paddock in the spring to take advantage of the rapid forage growth.

Q: With only have one acre of pasture, do I have room for rotational grazing paddocks?

If you have room, split your one acre in half and rotate between the two halves.

Q: I have several horses that don’t get along so cannot put them all in the same group for turnout. What should I do?

You can create more than one rotational system on the same farm. For example, you might divide half the pastureland into a system for the geldings, and the other half into a system for the mares. Put in as many different rotational systems as you need and have room for.

Q: My sheds aren’t in a suitable location to have a central sacrifice lot. What do you suggest?

There are endless possibilities for how to design a rotational grazing system. You can keep the sacrifice lot close to the barn and use laneways to access paddocks farther away. Another option is to graze individual pastures one at a time without a fully connected system. For this latter option, individual paddocks must have their own water source.

This small acreage was split into three sections for three horses, and manages to keep nice vegetation in each paddock. The large sacrifice lot in the foreground is used for turnout when the forage in the paddocks do not provide enough forage for grazing. Photo: Sarah Ralston.

Rotational grazing can meet the needs of horse farm managers, just as it works well for managers of many other types of livestock. No matter how you lay out your fields, the key is finding a way to give paddocks enough recovery time for forage to regrow.

The most important question to ask is: How did my pastures get in poor shape to begin with? If your pastures are in poor shape, it will be helpful to renovate by soil testing, liming, fertilizing, reseeding, etc. If the pastures are overgrazed, and you renovate them but don’t stop overgrazing, they will inevitably look the same in a short amount of time. Grazing management is crucial to maintaining lush, productive pastures that provide nutrition for your horses and benefit the environment by reducing erosion and filtering water. Rotational grazing is an effective way to take better care of pastures.

Related: Horse Fencing Fundamentals: Posts & Braces

Related: Safe and Functional Horse Fencing

The Penn State Extension Equine Team is a group of equine educators providing research-based information on equine health, nutrition, and pasture/environmental management. Serving the state of Pennsylvania, the team offers educational material to horse owners through publications, workshops, online courses, webinars, and consults.

Main Photo: Pam MacKenzie